Failure Was Not an Option: How Mission Control Saved Apollo 13

April 13, 1970: The Moment Everything Changed

Two hundred thousand miles from Earth, astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise drifted in the black vacuum of space, en route to the moon. It was meant to be NASA’s third lunar landing, another step in America’s relentless march toward space exploration. But at 9:08 p.m. Houston time, something went wrong.

A violent shudder. A sharp bang. Warning lights flickering to life.

Then, the words that would be seared into history: “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” (Nope, it wasn’t “Houston… we have a problem”!)

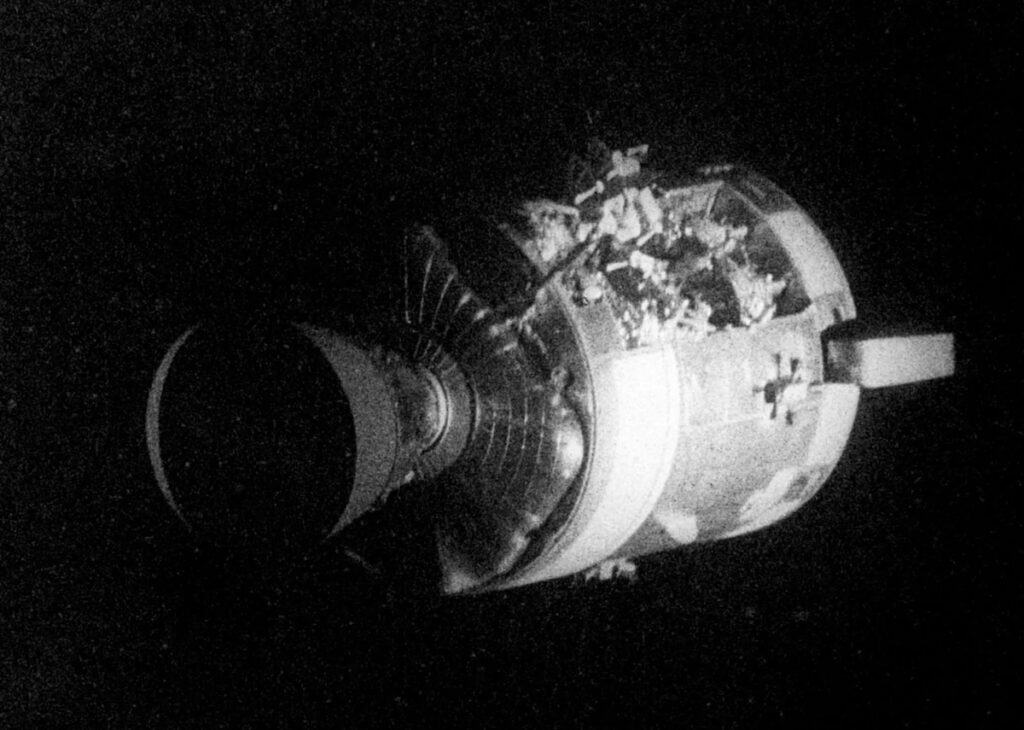

Inside NASA’s Mission Control Center, flight director Gene Kranz didn’t flinch. He was used to tension, to problems that came without warning. But this was different. The oxygen tank in the service module had exploded, crippling the spacecraft. Power was failing, oxygen was depleting, and the mission, originally intended to put men on the moon, was now a desperate struggle to bring them home.

There was no manual for this. No protocol. And no time.

The Man at the Helm: Gene Kranz and the Weight of Command

Gene Kranz wasn’t a scientist or an astronaut. He was a former fighter pilot with a reputation for unshakeable discipline, a leader forged in the fires of NASA’s early failures. He had been there for Apollo 1, when three astronauts died in a launchpad fire. He had seen what happened when NASA failed to anticipate disaster.

Failure was not an option. Not this time.

Kranz snapped into action. Mission Control, rows of engineers, mathematicians, and technicians, became a war room. Every problem had to be solved in real time. Every second mattered.

“Let’s work the problem, people,” Kranz told his team. “Let’s not make things worse by guessing.”

A Ship Without Power, A Crew Without Time

The explosion had left Apollo 13 critically damaged. Power reserves were dwindling. Carbon dioxide levels were rising. The command module, Odyssey, could no longer sustain the crew.

Kranz and his engineers made a radical decision: use the lunar module, Aquarius, as a makeshift lifeboat. It wasn’t built to support three men for days, but there was no alternative. They would shut down the command module, conserve energy and rely on ingenuity to stretch the spacecraft’s failing systems long enough to make it home.

The next problem: oxygen.

Square Peg, Round Hole: The Carbon Dioxide Crisis

Hours into the crisis, another lethal issue arose, carbon dioxide levels were climbing. The crew’s own breath was poisoning the small cabin, and the filters designed to remove CO₂ wouldn’t last. Worse, the filters from the command module, still functional, were square, while the lunar module’s filtration system was round.

The engineers at NASA had a serious challenge: How do you fit a square peg into a round hole, 200,000 miles from earth, with only the materials on board? The answer lay not in high-tech solutions but in sheer resourcefulness.

Using duct tape, plastic bags and cardboard ripped from a flight manual, the team on the ground constructed a makeshift adapter. Instructions were relayed to the crew, who followed them step by step, assembling the crude device in zero gravity. Against all odds, it worked, the CO₂ levels stabilized. The astronauts could breathe.

The Final Test: Surviving Re-Entry

With a crippled spacecraft and dwindling power, there was one final hurdle: re-entry. If Apollo 13’s angle was too shallow, the capsule would skip off Earth’s atmosphere and vanish into space. Too steep, and it would burn up on descent.

To make matters worse, re-entry always meant a period of radio silence as the capsule plunged through the atmosphere. It was supposed to last three minutes. But as Mission Control held its breath, three minutes passed. Then four. Then five.

Had Apollo 13 been lost?

And then, static. A voice broke through:

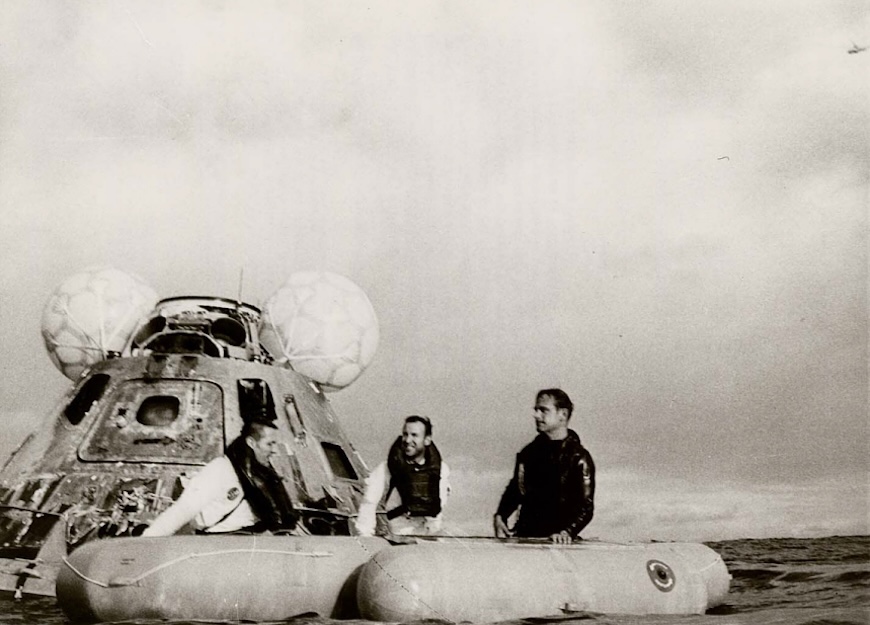

“Houston, this is Odyssey.”

Cheers erupted in Mission Control. The astronauts were alive. Apollo 13 had survived.

What Apollo 13 Taught the World About Information Flow

Apollo 13 was a failure in mission terms. The moon landing was abandoned. But in the broader sense, it was NASA’s finest hour. It was a testament to human ingenuity, to leadership under pressure and, perhaps most importantly, to the power of information management.

Gene Kranz and his team weren’t just solving problems; they were processing an overwhelming volume of constantly changing data. Oxygen levels, power reserves, trajectory calculations, CO₂ buildup—every decision depended on having accurate, real-time information and filtering out distractions. There was no room for misinformation. No tolerance for speculation.

This is what makes high-stakes decision-making possible. Whether in spaceflight, crisis response or corporate leadership, the ability to monitor, interpret and act on the right data at the right time can mean the difference between catastrophe and success.

Information Is the Lifeline of Decision-Making

NASA had a mission control room, where data from Apollo 13 was gathered, analyzed and acted upon in real time. Today, businesses and organizations face their own high-stakes environments—not in space, but in the public sphere, where misinformation, brand perception and media narratives evolve rapidly.

Having a real-time data intelligence system isn’t just a luxury; it’s essential. Just as Kranz’s team had to sift through thousands of data points to find solutions, modern organizations need tools that provide clarity in moments of uncertainty. Without it, they risk making decisions based on incomplete or outdated information.

Broadsight provides organizations with that clarity. In a landscape where reputation, public sentiment and media trends shift in real time, it acts as a modern-day mission control: allowing teams to track, analyze and respond with precision before minor issues become major crises.

Final Sign-Off: Don’t Let Your Brand Fly Blind

Apollo 13 survived because of the right data, the right decisions and the right leadership. Without a clear picture of the situation, things could have ended very differently.

Your organization might not be navigating deep space, but it is navigating the unknown. Broadsight keeps your brand’s mission on course, so you’re never caught unprepared. See it in action at broadsight.ca.

Receive our newsletter

Sign up below and we’ll be in touch with monthly updates about Broadsight, along with news and insights to keep you on the cutting edge of communications work in an AI era.