Apple’s Comeback is a Lesson in Speaking with One Voice

In the summer of 1997, Apple looked less like a technology company and more like a fading relic. Its stock had cratered. Its product line was a labyrinth of forgettable machines, each more confusing than the last. Industry analysts wrote eulogies in real time. Michael Dell, when asked what he would do if he were in charge of Apple, famously replied, “I’d shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders.”

Apple, instead, reached out to Steve Jobs.

Rebuilding from Within

Jobs had co-founded Apple, but by the time he returned, the company was nearly unrecognizable. Years of corporate infighting and unchecked expansion had left the brand bloated and unfocused. There were multiple versions of every computer. Marketing messages overlapped or contradicted one another. Few people could articulate what made Apple unique anymore. The company still had technical talent, but its identity had fractured.

Jobs didn’t respond with invention. He responded with subtraction. The leadership team scrapped over 70 percent of Apple’s offerings. Projects were shelved. Divisions were closed. The product catalog was reduced to a simple grid: consumer and pro, desktop and portable. But these operational decisions, while important, were not the foundation of the turnaround.

The foundation was narrative.

Jobs understood that people don’t just buy products. They buy meaning. And Apple’s meaning had been lost. What followed was not just a rebranding but a reintroduction.

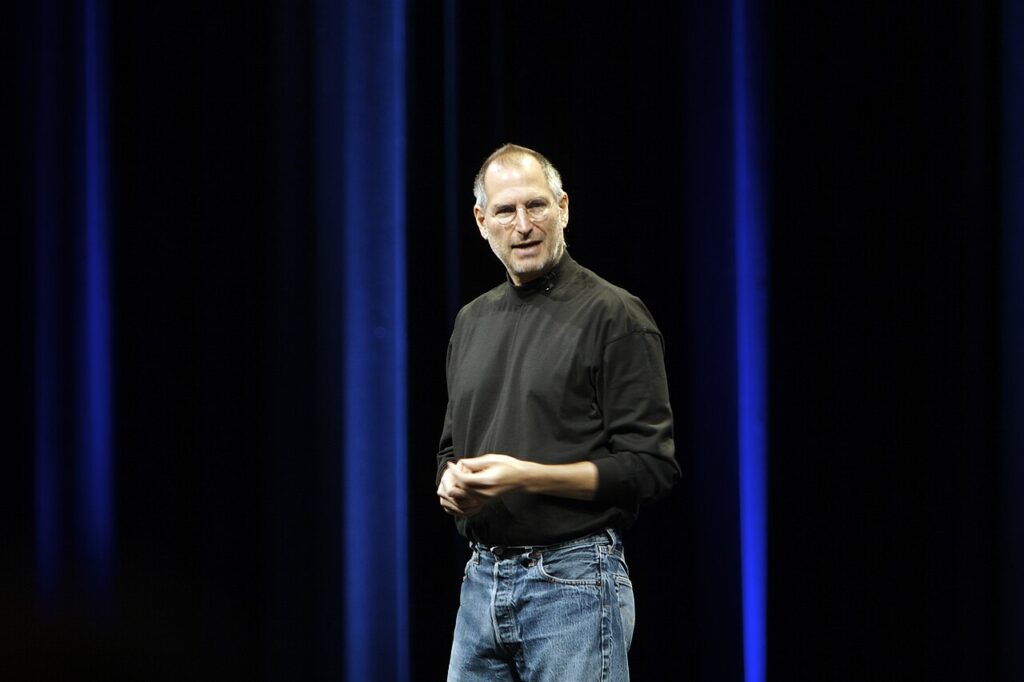

He also brought a different kind of leadership presence to the public stage. Jobs didn’t just represent the company; he embodied it. His keynote addresses, often delivered in jeans and a black turtleneck, became storytelling performances. He wasn’t reading from a script. He was delivering a belief system. One product announcement at a time, he rebuilt trust through tone, conviction and message control.

Internally, that consistency began to take root. Teams started speaking the same language. Engineers, marketers, sales leads and executives referenced the same guiding ideas. Jobs held regular communications reviews to ensure that every outbound message reinforced Apple’s repositioning. Even press releases were scrutinized for tone.

This wasn’t just a brand refresh. It was a culture reset, and it was made sustainable by the systems behind it.

The Underdog Reimagined

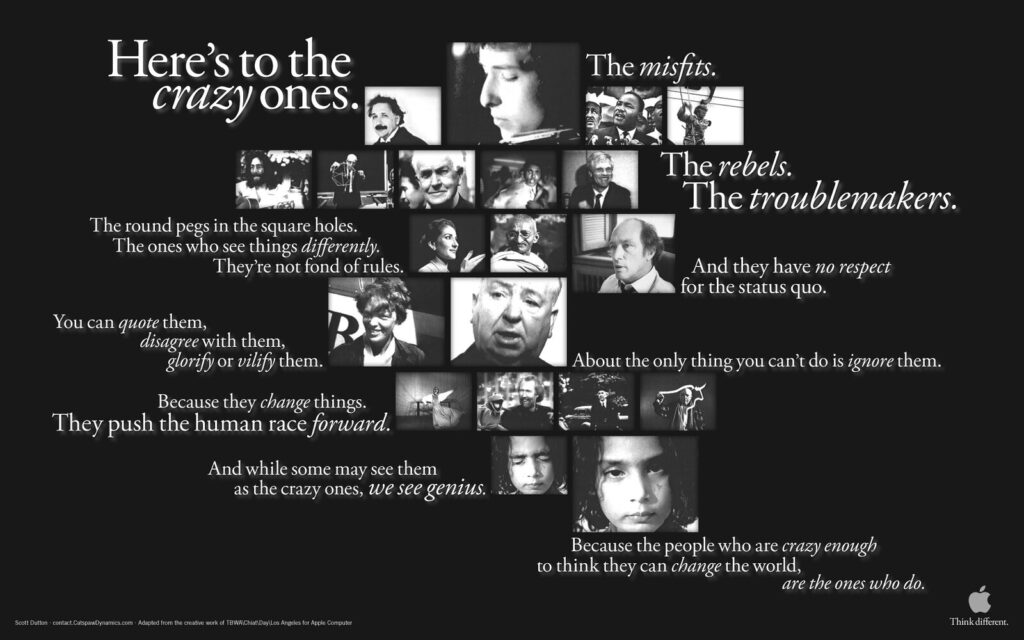

The “Think Different” campaign wasn’t about processors or screen resolution. It was about identity. The ads featured black-and-white images of rebels, visionaries and artists such as Gandhi, Einstein, Lennon and Earhart. The narration didn’t reference Apple until the final frame. It was an ode to people who challenged the status quo.

At a time when Apple was widely dismissed, the campaign worked not by denying the company’s decline but by reframing it. Apple cast itself as the underdog for those who saw the world differently. It didn’t try to be everything to everyone. It focused on those who wanted something distinct.

That focus had ripple effects. Macworld in 1998 didn’t just mark the debut of the iMac. It marked the return of Apple as a cultural player. The computer itself, a gumdrop-shaped burst of color, reinforced the campaign’s message without needing a word. This was not another beige box. This was a creative tool for people who didn’t want to follow the herd.

For PR and communications teams, this moment is instructive. Most companies, when facing existential challenges, respond by doing more. More content. More messaging. More offers. But Jobs chose to do less, and to ensure what they did do, they did with clarity. The internal messaging matched the public narrative. From press briefings to product launches, every message reinforced the same idea.

That kind of alignment requires more than inspiration. It requires coordination. Behind the scenes, teams need tools that let them track what was said, where it landed and how it was received. Not just for posterity but for precision. It is one thing to say the right thing in a keynote. It is another to ensure that message carries into every journalist interview, follow-up question and regional news story.

This kind of infrastructure has become essential for media teams navigating transformation. When every public statement, internal update or journalist inquiry has the potential to shape perception, the difference between confusion and clarity is often just a matter of coordination. Platforms like Broadsight exist to make that kind of precision possible, enabling teams to align their message across moments big and small.

Back in 1997, the media was not eager to give Apple the benefit of the doubt. Early press coverage following Jobs’s return was often skeptical. Some described the restructuring as a sign of desperation. Others mocked the company’s shrinking product line as a concession of defeat. But as the Think Different campaign rolled out and Jobs maintained message discipline across interviews and public appearances, sentiment began to shift. Columnists who had once predicted the company’s collapse started asking more thoughtful questions. Some even began framing Apple’s pivot as bold rather than reckless. That shift didn’t happen because of one ad. It happened because journalists were gradually given a consistent, coherent narrative to engage with.

That stands in sharp contrast to how many companies handle messaging today. In an era where corporate statements often feel reactive, fragmented or committee-written, Apple’s comeback feels unusually intentional. Brands today have more platforms, more stakeholders and more pressure to speak immediately rather than thoughtfully. In that environment, alignment often gives way to volume. But Apple’s story shows what can happen when a company steps back, regroups and speaks with one voice.

Apple eventually followed its messaging clarity with product brilliance. But the shift in perception began long before the first iMac hit shelves. It started when the company aligned its voice, internally and externally. That is the real legacy of the Think Different era. And it remains a powerful standard for every team hoping to turn a moment of instability into a foundation for relevance.

To learn how Broadsight can help your organization achieve clarity and narrative consistency at every touchpoint, visit Broadsight.ca.

Receive our newsletter

Sign up below and we’ll be in touch with monthly updates about Broadsight, along with news and insights to keep you on the cutting edge of communications work in an AI era.